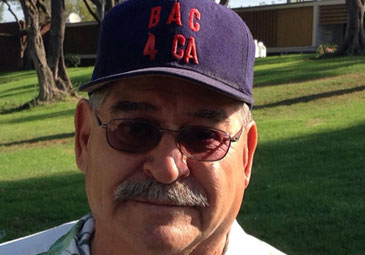

Robert Austin

Retired Nursing Attendant

"I go to the farmer's market and then I like to watch the ducks and the people."

Every city has its story. East LA has many.

"I go to the farmer's market and then I like to watch the ducks and the people."

"I was here everyday from before it opened till it closed. It's just home to me."

"You're gonna say you interviewed Jon Carmona before he made it to the big leagues."

"I have four kids, as you can see, and we come on weekends for all the interactive games."

"It's been a good life, you know. I'm 75 and, if I'm lucky, I'll have another five left in me."

"Squad, Assemble!"

There's something for everyone in East LA's historic public park.

BELVEDERE PARK, East Los Angeles -- Have you ever walked through the park and counted the number of unique individuals you see? Not just "unique" in the way that parks tend to house some of the city's most eccentric characters, but unique in the sense of varying ages, ethnicities, socioeconomic classes and backgrounds.

Public parks have a way of bringing together the most eclectic groups of community members. It goes with the motto that any and everyone is welcome on the public land.

East Los Angeles' population is already unique in its own right. Though the city of Los Angeles is one of the most diverse in the world, the community of East LA is 96.7-percent Latino, one of the highest concentrations in the United States, according to a project mapping Los Angeles ethnicities by the LA Times.

Many of East LA's residents frequent Belvedere Park, located by the East LA Public Library and Civic Center. The park is actually of historic importance to the Latino community, as a symbol of Mexican fragmentation and displacement in Los Angeles.

Belvedere Park spans nearly 31 acres across the heart of East LA, but is bisected by The 60 Pomona Freeway. The controversial freeway program cut through many predominantly Mexican communities in the neighborhood, and requires a pedestrian overpass to connect the two sections of the park.

Today, a quick stroll past the man-made lake or through the various playing fields will yield countless signs of Latino influence.

"Often, there are families celebrating their daughters' quinceañeras," said Robert Austin, a retired nursing assistant who comes to the park once a week for the farmers' market. "It's usually every week, it seems."

Street vendors sell frozen "helados"--icy, fruit-based Mexican treats--to families and children in the park, calling out in Spanish and ringing bells strapped to their carts.

Orlando Villavicencio and his four young children are prime targets for those vendors. The native of Baja, Mexico moved to East LA and brings his kids to the park's playground every weekend, similar to many families in the area.

"There are usually a lot of [vendors] on weekends, especially Sunday after church," said Villavicencio.

The vendors tend to congregate near the playgrounds and ball fields, honing in on the number of large families and children running around.

"It's basically families here," said Villavicencio. "Parents and little kids playing around, and they can enjoy ice cream and snacks here in the park."

The athletic fields--of which Belvedere Park boasts a multitude, ranging from soccer and baseball to a pair of basketball courts--also tend to showcase the community's cultural background. The Spanish on the sandlot has actually been around for decades, ranging back to Los Chorizeros, East LA's semi-professional baseball club from the 1940s-1970s, which held its home games at Belvedere Park.

But despite its location in such a dense Latino community, visitors say Belvedere Park's clientele varies greatly.

"It's very diverse for being in a very Mexican-cultured place," said Jonathan Carmona, a sophomore at Garfield High School. Carmona plays basketball every day, switching between the gym and the outdoor courts in Belvedere Park.

Carmona usually plays at Belvedere Park on weekends to offset his weekday practice schedule, but when he does come, there is usually a good turnout.

"During the weekdays, it's not that full," said Carmona. "I usually have basketball practice so I'm not really here most of the time, but when we don't [have practice], there are usually people here."

However, really understanding the park's influence requires looking beyond the weekend warriors and through the eyes of an everyday visitor.

A young 21-year-old skateboarder, who goes by the nickname "Froggy", used to come every day as a child since Belvedere Skatepark was added to the recreational area in 2006.

"Once this park started getting built, I used to skate it," said Froggy. "And once it opened, I never left."

He would spend his entire day at the park, arriving before it opened in the morning and staying till it was too dark to skate. Belvedere Skatepark has earned praise throughout the skateboarding community as one of the top skateparks in all of Southern California, famous for its deep skate bowls that attract hundreds of pool skaters.

But it's not the deep bowls or the large ramps that keep bringing Froggy back. And it's likely not the ducks in Belvedere Park Lake or superior hoops and playgrounds that keep the rest of the community returning.

It's a broader, intangible connection the park has with the community.

"It's just home," said Froggy. "You can't really explain it. The people here, the things that happen--it's just home."